How Would We Avoid Crusades Happen Again Armed Forces

The Crusades

The Crusades were war machine campaigns sanctioned past the Roman Catholic Church during the High and Tardily Heart Ages.

Learning Objectives

Describe the origins of the Crusades

Cardinal Takeaways

Primal Points

- The Crusades were a series of military machine conflicts conducted by Christian knights to defend Christians and the Christian empire against Muslim forces.

- The Holy Country was part of the Roman Empire until the Islamic conquests of the 7th and 8th centuries. Thereafter, Christians were permitted to visit parts of the Holy Country until 1071, when Christian pilgrimages were stopped by the Seljuq Turks.

- The Seljuq Turks had taken over much of Byzantium afterward the Byzantine defeat at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071.

- In 1095 at the Quango of Piacenza, Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos requested military aid from Urban II to fight the Turks.

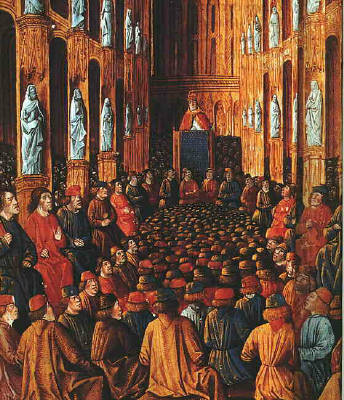

- In July 1095, Urban turned to his homeland of France to recruit men for the expedition. His travels there culminated in the Council of Clermont in November, where he gave speeches combining the idea of pilgrimage to the Holy Land with that of waging a holy war against infidels, which received an enthusiastic response.

Central Terms

- Seljuq Empire: A medieval Turko-Persian Sunni Muslim empire that controlled a vast area stretching from the Hindu Kush to eastern Anatolia and from Central Asia to the Persian Gulf. The Seljuq Turk attack on Byzantium helped spur the crusades.

- heretical: Relating to difference from established beliefs or customs.

- Byzantine Empire: The predominantly Greek-speaking continuation of the eastern half of the Roman Empire during Late Artifact and the Center Ages.

- schism: A sectionalization or a split, usually betwixt groups belonging to a religious denomination.

The Crusades were a series of military conflicts conducted by Christian knights for the defense of Christians and for the expansion of Christian domains between the 11th and 15th centuries. By and large, the Crusades refer to the campaigns in the Holy Land sponsored past the papacy against Muslim forces. There were other crusades against Islamic forces in southern Spain, southern Italy, and Sicily, as well as campaigns of Teutonic knights confronting heathen strongholds in Eastern Europe. A few crusades, such equally the 4th Crusade, were waged within Christendom against groups that were considered heretical and schismatic. Crusades were fought for many reasons—to capture Jerusalem, recapture Christian territory, or defend Christians in non-Christian lands; every bit a ways of conflict resolution among Roman Catholics; for political or territorial advantage; and to gainsay paganism and heresy.

Origin of the Crusades

The origin of the Crusades in general, and especially of the First Crusade, is widely debated amid historians. The confusion is partially due to the numerous armies in the Offset Cause, and their lack of direct unity. The similar ideologies held the armies to similar goals, simply the connections were rarely strong, and unity broke down oftentimes. The Crusades are most normally linked to the political and social situation in 11th-century Europe, the rise of a reform movement within the papacy, and the political and religious confrontation of Christianity and Islam in Europe and the Middle East. Christianity had spread throughout Europe, Africa, and the Eye E in Late Antiquity, but past the early 8th century Christian rule had become limited to Europe and Anatolia later the Muslim conquests.

Background in Europe

The Holy Land had been part of the Roman Empire, and thus the Byzantine Empire, until the Islamic conquests. In the 7th and eighth centuries, Islam was introduced in the Arabian Peninsula past the Islamic prophet Muhammad and his followers. This formed a unified Muslim polity, which led to a rapid expansion of Arab power, the influence of which stretched from the northwest Indian subcontinent, across Central Asia, the Middle E, North Africa, southern Italia, and the Iberian Peninsula, to the Pyrenees. Tolerance, merchandise, and political relationships between the Arabs and the Christian states of Europe waxed and waned. For example, the Fatimid caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah destroyed the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, but his successor immune the Byzantine Empire to rebuild information technology. Pilgrimages by Catholics to sacred sites were permitted, resident Christians were given certain legal rights and protections under Dhimmi status, and interfaith marriages were not uncommon. Cultures and creeds coexisted and competed, but the frontier conditions became increasingly inhospitable to Catholic pilgrims and merchants.

At the western edge of Europe and of Islamic expansion, the Reconquista (recapture of the Iberian Peninsula from the Muslims) was well underway by the 11th century, reaching its turning bespeak in 1085 when Alfonso VI of León and Castile retook Toledo from Muslim rule. Increasingly in the 11th century, strange knights, more often than not from French republic, visited Iberia to assist the Christians in their efforts.

The centre of Western Europe had been stabilized later on the Christianization of the Saxon, Viking, and Hungarian peoples by the cease of the tenth century. All the same, the breakup of the Carolingian Empire gave rise to an entire class of warriors who now had little to do merely fight amongst themselves. The random violence of the knightly grade was regularly condemned past the church, and and so it established the Peace and Truce of God to prohibit fighting on certain days of the year.

At the aforementioned time, the reform-minded papacy came into disharmonize with the Holy Roman Emperors, resulting in the Investiture Controversy. The papacy began to assert its independence from secular rulers, marshaling arguments for the proper utilise of armed force by Catholics. Popes such every bit Gregory 7 justified the subsequent warfare confronting the emperor's partisans in theological terms. It became adequate for the pope to utilise knights in the name of Christendom, not simply confronting political enemies of the papacy, but likewise against Al-Andalus, or, theoretically, against the Seljuq dynasty in the east. The result was intense piety, an involvement in religious affairs, and religious propaganda advocating a merely state of war to reclaim Palestine from the Muslims. Participation in such a war was seen as a class of penance that could weigh sin.

Aid to Byzantium

To the due east of Europe lay the Byzantine Empire, composed of Christians who had long followed a split Orthodox rite; the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches had been in schism since 1054. Historians have argued that the desire to impose Roman church authority in the e may have been one of the goals of the Crusades, although Urban II, who launched the First Crusade, never refers to such a goal in his messages on crusading. The Seljuq Empire had taken over about all of Anatolia later the Byzantine defeat at the Boxing of Manzikert in 1071; however, their conquests were piecemeal and led by semi-independent warlords, rather than past the sultan. A dramatic collapse of the empire'southward position on the eve of the Council of Clermont brought Byzantium to the brink of disaster. By the mid-1090s, the Byzantine Empire was largely confined to Balkan Europe and the northwestern fringe of Anatolia, and faced Norman enemies in the west likewise as Turks in the east. In response to the defeat at Manzikert and subsequent Byzantine losses in Anatolia in 1074, Pope Gregory Vii had called for the milites Christi ("soldiers of Christ") to go to Byzantium's aid.

Seljuq Empire: The Great Seljuq Empire at its greatest extent (1092).

Seljuq Empire: The Great Seljuq Empire at its greatest extent (1092).

While the Crusades had causes deeply rooted in the social and political situations of 11th-century Europe, the event actually triggering the First Crusade was a request for assistance from Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos. Alexios was worried most the advances of the Seljuqs, who had reached equally far west as Nicaea, non far from Constantinople. In March 1095, Alexios sent envoys to the Council of Piacenza to inquire Pope Urban II for assistance against the Turks.

Urban responded favorably, perhaps hoping to heal the Smashing Schism of xl years earlier, and to reunite the Church building under papal primacy by helping the eastern churches in their fourth dimension of need. Alexios and Urban had previously been in close contact in 1089 and later on, and had openly discussed the prospect of the (re)matrimony of the Christian church building. There were signs of considerable co-operation between Rome and Constantinople in the years immediately before the Crusade.

In July 1095, Urban turned to his homeland of France to recruit men for the expedition. His travels there culminated in the Council of Clermont in November, where, according to the various speeches attributed to him, he gave an impassioned sermon to a large audience of French nobles and clergy, graphically detailing the fantastical atrocities existence committed against pilgrims and eastern Christians. Urban talked almost the violence of European society and the necessity of maintaining the Peace of God; almost helping the Greeks, who had asked for assistance; about the crimes being committed confronting Christians in the east; and about a new kind of war, an armed pilgrimage, and of rewards in heaven, where remission of sins was offered to any who might dice in the undertaking. Combining the idea of pilgrimage to the Holy Land with that of waging a holy state of war against infidels, Urban received an enthusiastic response to his speeches and soon after began collecting military forces to brainstorm the First Crusade.

The First Crusade

The First Cause (1095–1099) was a military expedition by Roman Catholic Europe to regain the Holy Lands taken in Muslim conquests, ultimately resulting in the recapture of Jerusalem.

Learning Objectives

Evaluate the events of the First Cause

Key Takeaways

Cardinal Points

- The Beginning Crusade (1095–1099), called for past Pope Urban Ii, was the first of a number of crusades that attempted to recapture the Holy Lands.

- It was launched on November 27, 1095, by Pope Urban II with the primary goal of responding to an appeal from Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos, who had been defeated past Turkish forces.

- An additional goal shortly became the chief objective—the Christian reconquest of the sacred urban center of Jerusalem and the Holy Land and the freeing of the Eastern Christians from Muslim dominion.

- The first object of the entrada was Nicaea, previously a city under Byzantine rule, which the Crusaders captured on June 18, 1097, by defeating the troops of Kilij Arslan.

- Subsequently marching through the Mediterranean region, the Crusaders arrived at Jerusalem, launched an assault on the urban center, and captured information technology in July 1099, massacring many of the metropolis's Muslim and Jewish inhabitants.

- In the end, they established the crusader states of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the County of Tripoli, the Principality of Antioch, and the Canton of Edessa.

Cardinal Terms

- Church of the Holy Sepulchre: A church within the Christian Quarter of the Old Metropolis of Jerusalem that contains, according to traditions dating back to at least the 4th century, the two holiest sites in Christendom—the site where Jesus of Nazareth was crucified and Jesus'southward empty tomb, where he is said to have been buried and resurrected.

- Pope Urban Two: Pope from March 12, 1088, to his death in 1099, he is best known for initiating the Starting time Cause.

- People'southward Crusade: An expedition seen as the prelude to the First Cause that lasted roughly half-dozen months, from April to Oct 1096, and was led mostly by peasants.

- Alexios I Komnenos: Byzantine emperor from 1081 to 1118, whose appeals to Western Europe for aid against the Turks were too the catalyst that likely contributed to the convoking of the Crusades.

Overview

The First Crusade (1095–1099), chosen for by Pope Urban II, was the first of a number of crusades intended to recapture the Holy Lands. Information technology started equally a widespread pilgrimage in western Christendom and ended equally a armed forces expedition past Roman Cosmic Europe to regain the Holy Lands taken in the Muslim conquests of the Mediterranean (632–661), ultimately resulting in the recapture of Jerusalem in 1099.

It was launched on November 27, 1095, by Pope Urban 2 with the primary goal of responding to an appeal from Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos, who requested that western volunteers come to his assistance and help to repel the invading Seljuq Turks from Anatolia (modern-twenty-four hour period Turkey). An boosted goal before long became the principal objective—the Christian reconquest of the sacred city of Jerusalem and the Holy Land and the freeing of the Eastern Christians from Muslim rule.

During the cause, knights, peasants, and serfs from many regions of Western Europe travelled over land and by sea, first to Constantinople and and then on toward Jerusalem. The Crusaders arrived at Jerusalem, launched an assault on the urban center, and captured information technology in July 1099, massacring many of the city'southward Muslim and Jewish inhabitants. They also established the crusader states of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the County of Tripoli, the Principality of Antioch, and the County of Edessa.

People'southward Cause

Pope Urban II planned the departure of the cause for August 15, 1096; earlier this, a number of unexpected bands of peasants and depression-ranking knights organized and set off for Jerusalem on their own, on an expedition known as the People's Cause, led by a monk named Peter the Hermit. The peasant population had been affected past drought, famine, and disease for many years before 1096, and some of them seem to take envisioned the crusade as an escape from these hardships. Spurring them on had been a number of meteorological occurrences starting time in 1095 that seemed to be a divine blessing for the motility—a meteor shower, an aurorae, a lunar eclipse, and a comet, amid other events. An outbreak of ergotism had too occurred simply before the Council of Clermont. Millenarianism, the belief that the end of the world was imminent, widespread in the early 11th century, experienced a resurgence in popularity. The response was beyond expectations; while Urban might have expected a few thousand knights, he ended up with a migration numbering upward to xl,000 Crusaders of mostly unskilled fighters, including women and children.

Lacking military discipline in what likely seemed a foreign land (Eastern Europe), Peter's fledgling army quickly found itself in trouble despite the fact that they were still in Christian territory. This unruly mob began to attack and pillage outside Constantinople in search of supplies and nutrient, prompting Alexios to hurriedly ferry the gathering across the Bosporus one week later. Subsequently crossing into Asia Pocket-size, the crusaders carve up upward and began to plunder the countryside, wandering into Seljuq territory around Nicaea, where they were massacred past an overwhelming group of Turks.

The Commencement Crusade

The 4 main Crusader armies left Europe around the appointed time in August 1096. They took unlike paths to Constantinople and gathered outside the city walls between November 1096 and April 1097; Hugh of Vermandois arrived start, followed by Godfrey, Raymond, and Bohemond. This time, Emperor Alexios was more prepared for the Crusaders; there were fewer incidents of violence along the way.

The Crusaders may have expected Alexios to become their leader, but he had no interest in joining them, and was mainly concerned with transporting them into Asia Pocket-size as chop-chop as possible. In return for food and supplies, Alexios requested that the leaders to swear fealty to him and hope to return to the Byzantine Empire whatever state recovered from the Turks. Before ensuring that the various armies were shuttled across the Bosporus, Alexios advised the leaders on how best to bargain with the Seljuq armies they would soon encounter.

Siege of Nicaea and March to Jerusalem

The Crusader armies crossed over into Asia Minor during the first half of 1097, where they were joined by Peter the Hermit and the residue of his little army. Alexios also sent 2 of his own generals, Manuel Boutoumites and Tatikios, to help the Crusaders. The first object of their campaign was Nicaea, previously a city nether Byzantine dominion, but which had become the capital of the Seljuq Sultanate of Rum under Kilij Arslan I. Arslan was away campaigning against the Danishmends in key Anatolia at the time, and had left backside his treasury and his family, underestimating the force of these new Crusaders.

Subsequently, upon the Crusaders' arrival, the city was subjected to a lengthy siege, and when Arslan had discussion of it he rushed dorsum to Nicaea and attacked the Crusader regular army on May 16. He was driven back by the unexpectedly big Crusader force, with heavy losses suffered on both sides in the ensuing boxing. The siege continued, but the Crusaders had piddling success every bit they found they could not blockade Lake Iznik, which the city was situated on, and from which it could be provisioned. To break the metropolis, Alexios had the Crusaders' ships rolled over land on logs, and at the sight of them the Turkish garrison finally surrendered, 18 June 18. The city was handed over to the Byzantine troops.

At the end of June, the Crusaders marched on through Anatolia. They were accompanied by some Byzantine troops under Tatikios, and still harbored the hope that Alexios would send a full Byzantine army after them. Later on a battle with Kilij Arslan, the Crusaders marched through Anatolia unopposed, simply the journey was unpleasant, as Arslan had burned and destroyed everything he left behind in his ground forces's flight. It was the middle of summer, and the Crusaders had very trivial nutrient and water; many men and horses died. Swain Christians sometimes gave them gifts of nutrient and money, but more often than not the Crusaders only looted and pillaged whenever the opportunity presented itself.

Proceeding downward the Mediterranean coast, the crusaders encountered fiddling resistance, as local rulers preferred to make peace with them and furnish them with supplies rather than fight.

Capture of Jerusalem

On June 7, the Crusaders reached Jerusalem, which had been recaptured from the Seljuqs by the Fatimids but the year before. Many Crusaders wept upon seeing the urban center they had journeyed so long to reach. The inflow at Jerusalem revealed an arid countryside, lacking in water or food supplies. Here there was no prospect of relief, even as they feared an imminent attack by the local Fatimid rulers. The Crusaders resolved to take the metropolis by attack. They might have been left with footling choice, as information technology has been estimated that merely almost 12,000 men, including 1,500 cavalry, remained by the fourth dimension the army reached Jerusalem.

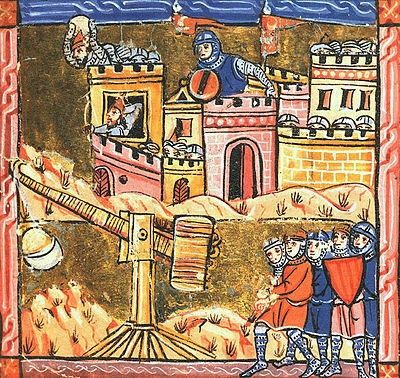

After the failure of the initial assault, a meeting between the various leaders was organized in which it was agreed upon that a more concerted attack would be required in the time to come. On June 17, a political party of Genoese mariners nether Guglielmo Embriaco arrived at Jaffa and provided the Crusaders with skilled engineers, and perhaps more than critically, supplies of timber (cannibalized from the ships) with which to build siege engines. The Crusaders' morale was raised when a priest, Peter Desiderius, claimed to take had a divine vision of Bishop Adhemar instructing them to fast and so march in a barefoot procession around the city walls, afterward which the city would fall, following the Biblical story of Joshua at the siege of Jericho.

The final assault on Jerusalem began on July xiii; Raymond'southward troops attacked the south gate while the other contingents attacked the northern wall. Initially the Provençals at the southern gate made little headway, but the contingents at the northern wall fared better, with a deadening but steady attrition of the defense. On July 15, a final push was launched at both ends of the city, and eventually the inner rampart of the northern wall was captured. In the ensuing panic, the defenders abandoned the walls of the city at both ends, allowing the Crusaders to finally enter.

The massacre that followed the capture of Jerusalem has attained item notoriety, as a "juxtaposition of extreme violence and anguished organized religion." The eyewitness accounts from the Crusaders themselves get out little doubt that there was a great slaughter in the backwash of the siege. Yet, some historians propose that the scale of the massacre was exaggerated in afterwards medieval sources. The slaughter lasted a day; Muslims were indiscriminately killed, and Jews who had taken refuge in their synagogue died when information technology was burnt down by the Crusaders. The following mean solar day, Tancred's prisoners in the mosque were slaughtered. Nonetheless, information technology is clear that some Muslims and Jews of the city survived the massacre, either escaping or existence taken prisoner to be ransomed. The Eastern Christian population of the city had been expelled before the siege past the governor, and thus escaped the massacre.

On July 22, a quango was held in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre to plant a rex for the newly created Kingdom of Jerusalem. Raymond Iv of Toulouse and Godfrey of Burgoo were recognized every bit the leaders of the crusade and the siege of Jerusalem. Raymond was the wealthier and more than powerful of the two, simply at kickoff he refused to go rex, perhaps attempting to bear witness his piety and probably hoping that the other nobles would insist upon his election anyway. The more popular Godfrey did not hesitate like Raymond, and accepted a position equally secular leader.

Having captured Jerusalem and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the Crusaders had fulfilled their vow.

The Second Crusade

The Second Crusade (1147–1149) was the 2nd major crusade launched confronting Islam past Catholic Europe, started in response to the fall of the County of Edessa founded in the First Crusade; it was largely a failure for the Europeans.

Learning Objectives

Explain the successes and failures of the 2d Crusade

Fundamental Takeaways

Key Points

- The 2d Crusade was started in 1147 in response to the fall of the County of Edessa the previous year to the forces of Zengi; Edessa was founded during the First Crusade.

- The Second Crusade was led by two European kings— Louis Vii of French republic and Conrad 3 of Federal republic of germany.

- The German and French armies took separate routes to Anatolia, fighting skirmishes along the style, and both were defeated separately past the Seljuq Turks.

- Louis and Conrad and the remnants of their armies somewhen reached Jerusalem and participated in an sick-advised assault on Damascus in 1148.

- The Second Crusade was a failure for the Crusaders and a great victory for the Muslims.

Central Terms

- Moors: The Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily, and Malta during the Center Ages, who initially were Berber and Arab peoples of North African descent.

- Conrad 3: Starting time German king of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, who led troops in the 2d Crusade.

- Manuel I Komneno: A Byzantine Emperor of the twelfth century who reigned over a crucial turning point in the history of Byzantium and the Mediterranean, including the 2d Cause.

- Louis Vii: A Capetian male monarch of the Franks from 1137 until his death who led troops in the Second Crusade.

The 2d Crusade

The Second Crusade (1147–1149) was the second major crusade launched from Europe every bit a Catholic holy war confronting Islam. The Second Crusade was started in 1147 in response to the fall of the County of Edessa the previous year to the forces of Zengi. The county had been founded during the First Crusade by King Baldwin of Boulogne in 1098. While it was the start Crusader state to be founded, it was also the commencement to fall.

The 2d Crusade was announced by Pope Eugene III, and was the first of the crusades to be led by European kings, namely Louis Vii of France and Conrad 3 of Germany, who had help from a number of other European nobles. The armies of the two kings marched separately beyond Europe. After crossing Byzantine territory into Anatolia, both armies were separately defeated by the Seljuq Turks. The primary Western Christian source, Odo of Deuil, and Syriac Christian sources merits that the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Komnenos secretly hindered the Crusaders' progress, particularly in Anatolia, where he is alleged to accept deliberately ordered Turks to attack them. Louis and Conrad and the remnants of their armies reached Jerusalem and participated in an ill-brash attack on Damascus in 1148. The Crusade in the east was a failure for the Crusaders and a great victory for the Muslims. It would ultimately have a key influence on the fall of Jerusalem and requite rise to the Tertiary Cause at the end of the 12th century.

The only Christian success of the Second Crusade came to a combined forcefulness of 13,000 Flemish, Frisian, Norman, English language, Scottish, and German Crusaders in 1147. Traveling by send from England to the Holy State, the regular army stopped and helped the smaller (7,000) Portuguese army capture Lisbon, expelling its Moorish occupants.

Cause in the East

Joscelin Two had tried to take back Edessa, but Nur ad-Din defeated him in November 1146. On February 16, 1147, the French Crusaders met to talk over their route. The Germans had already decided to travel overland through Hungary, every bit the sea route was politically impractical because Roger II, king of Sicily, was an enemy of Conrad. Many of the French nobles distrusted the land route, which would take them through the Byzantine Empire, the reputation of which still suffered from the accounts of the First Crusaders. However, it was decided to follow Conrad, and to set out on June 15.

German Route

The German crusaders, accompanied by the papal legate and Cardinal Theodwin, intended to run into the French in Constantinople. Ottokar III of Styria joined Conrad at Vienna, and Conrad's enemy Géza II of Hungary allowed them to pass through unharmed. When the German army of 20,000 men arrived in Byzantine territory, Emperor Manuel I Komnenos feared they were going to attack him, and Byzantine troops were posted to ensure that at that place was no problem. On September x, the Germans arrived at Constantinople, where relations with Manuel were poor. In that location was a battle, later on which the Germans were convinced that they should cross into Asia Pocket-size equally speedily as possible.

In Asia Minor, Conrad decided not to await for the French, and marched towards Iconium, majuscule of the Seljuq Sultanate of Rûm. Conrad split his army into ii divisions. The authority of the Byzantine Empire in the western provinces of Asia Minor was more nominal than existent, with much of the provinces being a no-man's land controlled past Turkish nomads. Conrad underestimated the length of the march confronting Anatolia, and anyhow assumed that the authority of Emperor Manuel was greater in Anatolia than was in fact the case. Conrad took the knights and the best troops with him to march overland and sent the camp followers with Otto of Freising to follow the coastal road. The rex's contingent was most totally destroyed by the Seljuqs on October 25, 1147, at the second Battle of Dorylaeum.

French Route

The French crusaders departed from Metz in June 1147, led by Louis, Thierry of Alsace, Renaut I of Bar, Amadeus Three, Count of Savoy and his half-brother William V of Montferrat, William Vii of Auvergne, and others, forth with armies from Lorraine, Brittany, Burgundy, and Aquitaine. A force from Provence, led past Alphonse of Toulouse, chose to expect until Baronial and cross past body of water. At Worms, Louis joined with crusaders from Normandy and England.

They followed Conrad's route fairly peacefully, although Louis came into conflict with King Geza of Hungary when Geza discovered Louis had immune an attempted Hungarian usurper to join his army. Relations inside Byzantine territory were grim, and the Lorrainers, who had marched alee of the rest of the French, also came into conflict with the slower Germans whom they met on the way.

The French met the remnants of Conrad's ground forces at Lopadion, and Conrad joined Louis's forcefulness. They followed Otto of Freising'due south route, moving closer to the Mediterranean coast, and they arrived at Ephesus in Dec, where they learned that the Turks were preparing to attack them. Manuel had sent ambassadors complaining about the pillaging and plundering that Louis had done forth the style, and at that place was no guarantee that the Byzantines would assist them against the Turks. Meanwhile, Conrad fell sick and returned to Constantinople, where Manuel attended to him personally, and Louis, paying no attention to the warnings of a Turkish attack, marched out from Ephesus with the French and German survivors. The Turks were indeed waiting to attack, simply in a small-scale battle exterior Ephesus, the French and Germans were victorious.

They reached Laodicea on the Lycus early in January 1148, effectually the same time Otto of Freising's army had been destroyed in the same area. Afterwards resuming the march, the vanguard under Amadeus of Savoy was separated from the residual of the regular army at Mount Cadmus, and Louis's troops suffered heavy losses from the Turks. Subsequently existence delayed for a month past storms, most of the promised ships from Provence did not go far at all. Louis and his associates claimed the ships that did make it for themselves, while the rest of the army had to resume the long march to Antioch. The army was almost entirely destroyed, either by the Turks or past sickness.

Siege of Damascus

The remains of the German language and French armies eventually continued on to Jerusalem, where they planned an attack on the Muslim forces in Damascus. The Crusaders decided to assault Damascus from the west, where orchards would provide them with a constant food supply. They arrived at Daraiya on July 23. The following day, the well-prepared Muslims constantly attacked the army advancing through the orchards outside Damascus. The defenders had sought help from Saif ad-Din Ghazi I of Mosul and Nur ad-Din of Aleppo, who personally led an attack on the Crusader army camp. The Crusaders were pushed back from the walls into the orchards, where they were prone to ambushes and guerrilla attacks.

Co-ordinate to William of Tyre, on July 27 the Crusaders decided to motility to the plain on the eastern side of the city, which was less heavily fortified, but also had much less food and water. Some records indicate that Unur had bribed the leaders to move to a less defensible position, and that Unur had promised to suspension off his alliance with Nur ad-Din if the Crusaders went home. Meanwhile, Nur ad-Din and Saif ad-Din had by now arrived. With Nur ad-Din in the field it was impossible for the Crusaders to return to their amend position. The local Crusader lords refused to carry on with the siege, and the iii kings had no choice but to abandon the urban center. First Conrad, then the residual of the army, decided to retreat to Jerusalem on July 28, and they were followed the whole way past Turkish archers, who constantly harassed them.

Backwash

Each of the Christian forces felt betrayed past the other. In Germany, the Crusade was seen as a huge debacle, with many monks writing that it could only have been the piece of work of the Devil. Despite the distaste for the retentiveness of the Second Crusade, the experience had notable touch on on High german literature, with many epic poems of the belatedly twelfth century featuring battle scenes conspicuously inspired past the fighting in the crusade. The cultural impact of the Second Crusade was even greater in French republic. Unlike Conrad, the Louis'due south image was improved past the crusade, with many of the French seeing him equally a suffering pilgrim male monarch who quietly bore God's punishments.

Relations between the Eastern Roman Empire and the French were badly damaged past the 2nd Crusade. Louis and other French leaders openly defendant Emperor Manuel I of colluding with Turkish attackers during the march across Asia Minor. The memory of the Second Crusade was to color French views of the Byzantines for the rest of the 12th and 13th centuries.

The Tertiary Cause

The Tertiary Crusade (1189–1192) was an attempt by European leaders to reconquer the Holy State from the Muslim sultan Saladin; information technology resulted in the capture of the important cities Acre and Jaffa, but failed to capture Jerusalem, the main motivation of the crusade.

Learning Objectives

Compare and contrast the Third Cause with the first two

Key Takeaways

Key Points

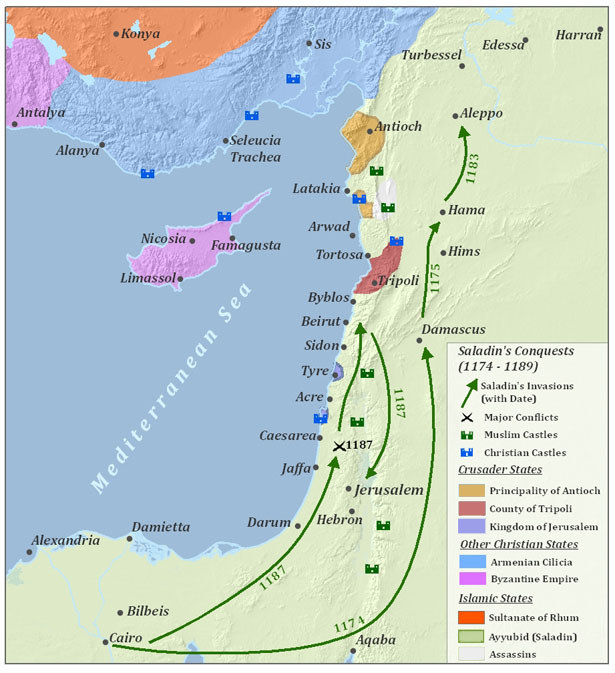

- After the failure of the 2d Crusade, the Zengid dynasty controlled a unified Syria and engaged in a successful conflict with the Fatimid rulers of Arab republic of egypt; the Egyptian and Syrian forces were ultimately unified under Saladin, who employed them to reduce the Christian states and recapture Jerusalem in 1187.

- The Crusaders, mainly nether the leadership of King Richard of England, captured Acre and Jaffa on their style to Jerusalem.

- Because of conflict with King Richard and to settle succession disputes, the German and French armies left the crusade early, weakening the Christian forces.

- After trying to overtake Jerusalem and having Jaffa change hands several times, Richard and Saladin finalized a treaty granting Muslim control over Jerusalem merely allowing unarmed Christian pilgrims and merchants to visit the city.

- The Third Crusade differed from the Start Crusade in several means: kings led the armies into battle, it was in response to European losses, and it resulted in a treaty.

Fundamental Terms

- Richard the Lionheart: King of England from July half dozen, 1189, until his death; famous for his reputation as a bang-up military leader and warrior.

- Saladin: The first sultan of Egypt and Syrian arab republic and the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty; he led the Muslim military campaign confronting the Crusader states in the Levant.

Overview

The Third Crusade (1189–1192), also known equally The Kings' Crusade, was an attempt by European leaders to reconquer the Holy Land from Saladin. The campaign was largely successful, capturing the important cities of Acre and Jaffa, and reversing virtually of Saladin's conquests, but information technology failed to capture Jerusalem, the emotional and spiritual motivation of the crusade.

After the failure of the Second Crusade, the Zengid dynasty controlled a unified Syrian arab republic and engaged in a conflict with the Fatimid rulers of Egypt. The Egyptian and Syrian forces were ultimately unified under Saladin, who employed them to reduce the Christian states and recapture Jerusalem in 1187. Spurred by religious zeal, King Henry Ii of England and King Philip II of French republic (known as Philip Augustus) ended their conflict with each other to lead a new crusade. The decease of Henry in 1189, however, meant the English contingent came nether the command of his successor, King Richard I of England (known equally Richard the Lionheart). The elderly Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa also responded to the call to arms, leading a massive regular army across Anatolia, but he drowned in a river in Asia Pocket-sized on June 10, 1190, earlier reaching the Holy Land. His death caused tremendous grief among the German language Crusaders, and most of his troops returned home.

Afterward the Crusaders had driven the Muslims from Acre, Philip and Frederick's successor, Leopold V, Duke of Austria (known as Leopold the Virtuous), left the Holy Land in August 1191. On September ii, 1192, Richard and Saladin finalized a treaty granting Muslim control over Jerusalem merely allowing unarmed Christian pilgrims and merchants to visit the urban center. Richard departed the Holy Land on October 2. The successes of the Third Cause allowed the Crusaders to maintain considerable states in Cyprus and on the Syrian coast. However, the failure to recapture Jerusalem would lead to the Fourth Cause.

Background

One of the major differences between the Beginning and 3rd Crusades is that by the fourth dimension of the Third Cause, and to a certain degree during the Second, the Muslim opponents had unified nether a single powerful leader. At the time of the First Crusade, the Middle Due east was severely divided by warring rulers. Without a unified front end opposing them, the Christian troops were able to conquer Jerusalem, as well equally the other Crusader states. Just under the powerful force of the Seljuq Turks during the Second Crusade and the even more unified power of Saladin during the Third, the Europeans were unable to attain their ultimate aim of holding Jerusalem.

Afterwards the failure of the Second Crusade, Nur advertisement-Din Zangi had control of Damascus and a unified Syrian arab republic. Nur ad-Din too took over Arab republic of egypt through an alliance, and appointed Saladin the sultan of these territories. After Nur advertisement-Din's death, Saladin also took over Acre and Jerusalem, thereby wresting command of Palestine from the Crusaders, who had conquered the expanse 88 years before. Pope Urban III is said to take complanate and died upon hearing this news, simply it is not really feasible that tidings of the fall of Jerusalem could have reached him by the fourth dimension he died, although he did know of the boxing of Hattin and the fall of Acre.

Siege of Acre

The Siege of Acre was one of the beginning confrontations of the 3rd Cause, and a central victory for the Crusaders but a serious defeat for Saladin, who had hoped to destroy the whole of the Crusader kingdom.

Richard arrived at Acre on June eight, 1191, and immediately began supervising the structure of siege weapons to assail the city, which was captured on July 12. Richard, Philip, and Leopold quarreled over the spoils of the victory. Richard cast downward the German flag from the city, slighting Leopold. The rest of the German language army returned home.

On July 31, Philip also returned home, to settle the succession in Vermandois and Flanders, and Richard was left in sole charge of the Christian expeditionary forces. Every bit in the Second Crusade, these disagreements and divisions within the European armies led to a weakening of the Christian forces.

Battle of Arsuf

After the capture of Acre, Richard decided to march to the city of Jaffa. Control of Jaffa was necessary before an assault on Jerusalem could be attempted. On September 7, 1191, however, Saladin attacked Richard's army at Arsuf, thirty miles due north of Jaffa. Richard then ordered a general counterattack, which won the battle. Arsuf was an of import victory. The Muslim army was not destroyed, despite the considerable casualties it suffered, but it was scattered; this was considered shameful by the Muslims and boosted the morale of the Crusaders. Richard was able to take, defend, and concord Jaffa, a strategically crucial motion toward securing Jerusalem. By depriving Saladin of the coast, Richard seriously threatened his hold on Jerusalem.

Advances on Jerusalem and Negotiations

Following his victory at Arsuf, Richard took Jaffa and established his new headquarters there. In November 1191 the Crusader army advanced inland toward Jerusalem. On December 12 Saladin was forced by force per unit area from his emirs to disband the greater part of his army. Learning this, Richard pushed his army forward, spending Christmas at Latrun. The army then marched to Beit Nuba, simply twelve miles from Jerusalem. Muslim morale in Jerusalem was so low that the arrival of the Crusaders would probably have caused the city to fall quickly. Appallingly bad weather—cold with heavy rain and hailstorms—combined with fear that if the Crusader ground forces besieged Jerusalem information technology might be trapped by a relieving force, led to the conclusion to retreat back to the coast. In July 1192, Saladin's ground forces suddenly attacked and captured Jaffa with thousands of men.

Richard was intending to return to England when he heard the news that Saladin and his army had captured Jaffa. Richard and a pocket-sized strength of little more than 2,000 men went to Jaffa past sea in a surprise assault. They stormed Jaffa from their ships and the Ayyubids, who had been unprepared for a naval attack, were driven from the city.

On September 2, 1192, following his defeat at Jaffa, Saladin was forced to finalize a treaty with Richard providing that Jerusalem would remain under Muslim control, but assuasive unarmed Christian pilgrims and traders to visit the city. The urban center of Ascalon was a contentious upshot, as it threatened communication betwixt Saladin'south dominions in Arab republic of egypt and Syrian arab republic; it was eventually agreed that Ascalon, with its defenses demolished, be returned to Saladin'southward control. Richard departed the Holy Country on October 9, 1192.

Aftermath and Comparisons

Neither side was entirely satisfied with the results of the state of war. Though Richard's victories had deprived the Muslims of of import coastal territories and re-established a feasible Frankish state in Palestine, many Christians in the Latin Due west felt disappointed that Richard had elected not to pursue the recapture of Jerusalem. Likewise, many in the Islamic world felt disturbed that Saladin had failed to bulldoze the Christians out of Syrian arab republic and Palestine. However, trade flourished throughout the Middle East and in port cities forth the Mediterranean coastline.

The motivations and results of the Third Cause differed from those of the First in several ways. Many historians contend that the motivations for the 3rd Crusade were more political than religious, thereby giving rise to the disagreements between the German, French, and English language armies throughout the crusade. By the stop, but Richard of England was left, and his pocket-size forcefulness was unable to finally overtake Saladin, despite successes at Acre and Jaffa. This infighting severely weakened the power of the European forces.

In addition, unlike the First Crusade, in the 2nd and Third Crusades kings led Crusaders into battle. The presence of European kings in battle set the armies upward for instability, for the monarchs had to ensure their own territories were not threatened during their absence. During the Third Crusade, both the German and French armies were forced to return abode to settle succession disputes and stabilize their kingdoms.

Furthermore, both the Second and 3rd Crusades were in response to European losses, kickoff the fall of the Kingdom of Edessa and so the fall of Jerusalem to Saladin. These defensive expeditions could exist seen as lacking the religious fervor and initiative of the First Crusade, which was entirely on the terms of the Christian armies.

Finally, the 3rd Crusade resulted in a treaty that left Jerusalem under Muslim rule merely allowed Christians access for trading and pilgrimage. In the past two crusades, the result had been to conquer and massacre or retreat, with no compromise or middle ground accomplished. Despite the understanding in the Third Crusade, the failure to overtake Jerusalem led to still some other cause soon later.

The Fourth Cause

Crusading became increasingly widespread in terms of geography and objectives during the 13th century and beyond, and crusades were aimed more at maintaining political and religious control over Europe than reclaiming the Holy Land.

Learning Objectives

Describe the failures of the 4th Crusade

Key Takeaways

Key Terms

- Crusader states: A number of mostly twelfth- and 13th-century feudal states created by Western European crusaders in Asia Minor, Hellenic republic, and the Holy Land, and in the eastern Baltic area during the Northern Crusades.

- Neat Schism: The break of communion between what are now the Eastern Orthodox and Catholic churches, which has lasted since the 11th century.

- Knights Templar: Among the wealthiest and most powerful of the Western Christian war machine orders; prominent actors in the Crusades.

- heretics: People who holds beliefs or theories that are strongly at variance with established behavior or customs, peculiarly those held by the Roman Cosmic Church building.

Development of the Crusades

The Crusades were a serial of religious wars undertaken by the Latin church building between the 11th and 15th centuries. Crusades were fought for many reasons: to capture Jerusalem, recapture Christian territory, or defend Christians in non-Christian lands; as a ways of conflict resolution among Roman Catholics; for political or territorial advantage; and to combat paganism and heresy.

The First Crusade arose afterwards a telephone call to arms in 1095 sermons by Pope Urban 2. Urban urged armed forces support for the Byzantine Empire and its Emperor, Alexios I, who needed reinforcements for his conflict with westward-migrating Turks in Anatolia. One of Urban's main aims was to guarantee pilgrims admission to the holy sites in the Holy State that were under Muslim control. Urban's wider strategy may have been to unite the eastern and western branches of Christendom, which had been divided since their carve up in 1054, and establish himself as caput of the unified church. Regardless of the motivation, the response to Urban's preaching by people of many different classes beyond Western Europe established the precedent for later crusades.

As a result of the First Crusade, four primary Crusader states were created: the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the County of Edessa, the Principality of Antioch, and the County of Tripoli. On a popular level, the First Crusade unleashed a moving ridge of impassioned, pious Catholic fury, which was expressed in the massacres of Jews that accompanied the Crusades and the violent treatment of the "schismatic" Orthodox Christians of the due east.

Nether the papacies of Calixtus II, Honorius Two, Eugenius III, and Innocent Two, smaller-calibration crusading connected around the Crusader states in the early 12th century. The Knights Templar were recognized, and grants of crusading indulgences to those who opposed papal enemies are seen by some historians every bit the showtime of politically motivated crusades. The loss of Edessa in 1144 to Imad ad-Din Zengi led to preaching for what subsequently became known as the Second Crusade. Rex Louis VII and Conrad III led armies from France and Germany to Jerusalem and Damascus without winning any major victories. Bernard of Clairvaux, who had encouraged the Second Cause in his preachings, was upset with the violence and slaughter directed toward the Jewish population of the Rhineland.

In 1187 Saladin united the enemies of the Crusader states, was victorious at the Boxing of Hattin, and retook Jerusalem. According to Benedict of Peterborough, Pope Urban 3 died of deep sadness on October xix, 1187, upon hearing news of the defeat. His successor, Pope Gregory VIII, issued a papal bull that proposed a third crusade to recapture Jerusalem. This crusade failed to win control of Jerusalem from the Muslims, but did outcome in a treaty that allowed trading and pilgrimage at that place for Europeans.

Crusading became increasingly widespread in terms of geography and objectives during the 13th century; crusades were aimed at maintaining political and religious command over Europe and across and were not exclusively focused on the Holy State. In Northern Europe the Catholic church building continued to battle peoples whom they considered pagans; Popes such as Celestine III, Innocent III, Honorius III, and Gregory IX preached crusade against the Livonians, Prussians, and Russians. In the early 13th century, Albert of Riga established Riga as the seat of the Bishopric of Riga and formed the Livonian Brothers of the Sword to catechumen the pagans to Catholicism and protect German commerce.

Fourth Crusade

Innocent Iii began preaching what became the Fourth Cause in 1200 in France, England, and Federal republic of germany, but primarily in France. The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Western European armed expedition originally intended to conquer Muslim-controlled Jerusalem by ways of an invasion through Egypt. Instead, a sequence of events culminated in the Crusaders sacking the urban center of Constantinople, the capital letter of the Christian-controlled Byzantine Empire. The Fourth Crusade never came to inside ane,000 miles of its objective of Jerusalem, instead conquering Byzantium twice before being routed by the Bulgars at Adrianople.

In January 1203, en route to Jerusalem, the majority of the Crusader leadership entered into an understanding with the Byzantine prince Alexios Angelos to divert to Constantinople and restore his deposed father as emperor. The intention of the Crusaders was then to continue to the Holy Land with promised Byzantine financial and military assist. On June 23, 1203, the main Crusader fleet reached Constantinople. Smaller contingents continued to Acre.

In August 1203, following clashes outside Constantinople, Alexios Angelos was crowned co-emperor (as Alexios 4 Angelos) with Crusader back up. Nonetheless, in January 1204, he was deposed past a popular uprising in Constantinople. The Western Crusaders were no longer able to receive their promised payments, and when Alexios was murdered on February viii, 1204, the Crusaders and Venetians decided on the outright conquest of Constantinople. In April 1204, they captured and brutally sacked the city and set up a new Latin Empire, besides every bit partitioned other Byzantine territories among themselves.

Byzantine resistance based in unconquered sections of the empire such as Nicaea, Trebizond, and Epirus ultimately recovered Constantinople in 1261.

The Fourth Cause is considered to be one of the final acts in the Keen Schism between the Eastern Orthodox Church and Roman Catholic Church, and a key turning signal in the decline of the Byzantine Empire and Christianity in the Nigh East.

After Crusades

After the failure of the Quaternary Crusade to hold Constantinople or achieve Jerusalem, Innocent III launched the first crusade against heretics, the Albigensian Crusade, against the Cathars in French republic and the County of Toulouse. Over the early decades of the century the Cathars were driven clandestine while the French monarchy asserted control over the region. Andrew II of Hungary waged the Bosnian Crusade confronting the Bosnian church, which was theologically Catholic only in long-term schism with the Roman Catholic Church building. The conflict only concluded with the Mongol invasion of Republic of hungary in 1241. In the Iberian peninsula, Crusader privileges were given to those aiding the Templars, the Hospitallers, and the Iberian orders that merged with the Club of Calatrava and the Order of Santiago. The papacy alleged frequent Iberian crusades, and from 1212 to 1265 the Christian kingdoms drove the Muslims back to the Emirate of Granada, which held out until 1492, when the Muslims and Jews were expelled from the peninsula.

Effectually this fourth dimension, popularity and energy for the Crusades declined. 1 factor in the decline was the disunity and conflict among Latin Christian interests in the eastern Mediterranean. Pope Martin Four compromised the papacy by supporting Charles of Anjou, and tarnished its spiritual luster with botched secular "crusades" against Sicily and Aragon. The collapse of the papacy'due south moral authority and the rise of nationalism rang the decease knell for crusading, ultimately leading to the Avignon Papacy and the Western Schism. The mainland Crusader states were extinguished with the fall of Tripoli in 1289 and the autumn of Acre in 1291.

Centuries afterward, during the centre of the 15th century, the Latin church tried to organize a new crusade aimed at restoring the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire, which was gradually existence torn down past the advancing Ottoman Turks. The effort failed, all the same, every bit the vast majority of Greek civilians and a growing office of their clergy refused to recognize and take the curt-lived near-union of the churches of East and West signed at the Quango of Florence and Ferrara by the Ecumenical patriarch Joseph II of Constantinople. The Greek population, reacting to the Latin conquest, believed that the Byzantine civilization that revolved around the Orthodox organized religion would be more than secure under Ottoman Islamic rule. Overall, religious-observant Greeks preferred to sacrifice their political liberty and political independence in social club to preserve their faith's traditions and rituals in separation from the Roman See.

In the tardily-14th and early-15th centuries, "crusades" on a limited scale were organized by the kingdoms of Hungary, Poland, Wallachia, and Serbia. These were not the traditional expeditions aimed at the recovery of Jerusalem simply rather defensive campaigns intended to prevent further expansion to the west by the Ottoman Empire.

Licenses and Attributions

Source: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-worldhistory/chapter/the-crusades/

0 Response to "How Would We Avoid Crusades Happen Again Armed Forces"

Post a Comment